I was working in a middle school classroom in Harlem on a problem called “chairs and tables.” It is a classic problem:

The Italian Villa Restaurant has square tables that the servers can push together to create longer tables and seat larger groups of customers. One one chair fits along a side of the square table.

![]()

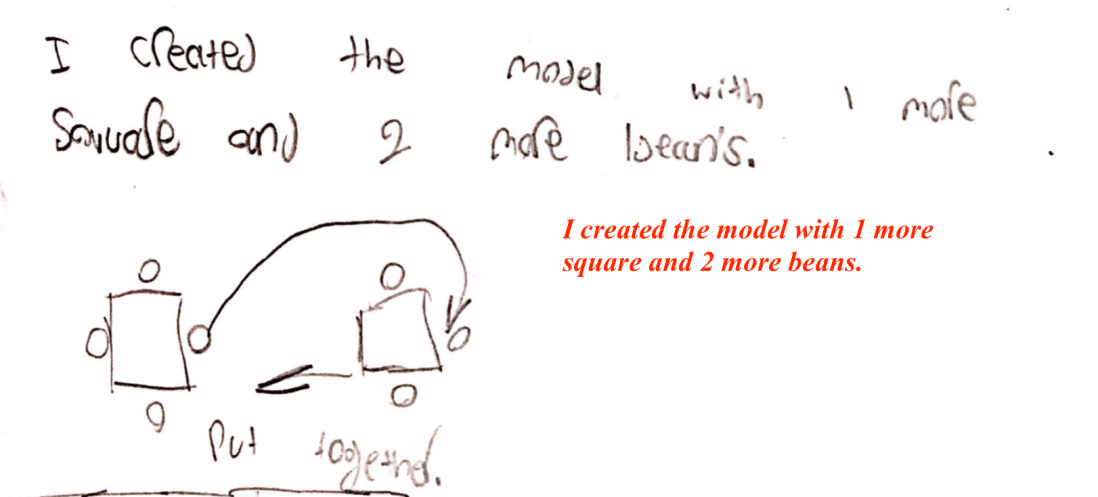

Students were invited to model the problem using flat tiles and dried black beans. Each bean represented a person in a chair and each tile represented a table. Students played with the model for a little while and shared how they would lengthen tables and add more chairs. Here is an example of how one child thought about the problem:

As seen in the image, the student envisions moving the chair on the right around to the side of the second table, adding two chairs to the top and bottom of the second table, and then the tables get “put together.”

Students worked on solving and creating an algebraic rule for the problem, based on building the model and then keeping track of the data on growing patterns in a t-chart. Most students found the rule 2t + 2, where t=tables. The purpose of the task was to model a pattern and make the leap to algebraic representations for tables of any length.

I could go on and on about marvelous and brilliant student strategies for solving this problem. The most important moment in working on this lesson for me as an educator took place during a conversation I had with one student named Damon. Damon was perplexed by this problem and struggled to model the addition of a square table to the existing table. To step back a moment, I started the problem by having students share about a time that they went out to a restaurant to eat with their families, and we talked about how sometimes we might see the servers moving tables together so that families could be together. To Damon, this problem presented a challenge that did not match his lived experience and caused an obstacle to seeing the problem as described.

Damon worked and worked, and kept adding four chairs every time he added a table. I asked him to restate the rule governing the problem, that there could only be one chair on one length of the square. But Damon insisted, “just put the extra person between the tables, they can fit.” To Damon, it was unthinkable that the servers would leave two people out every time they moved tables together. When we described the problem and asked students to envision the act of putting tables together, Damon envisioned his family and he was not thinking in chairs and tables, he was thinking about people. If there are already people sitting around a table, and then we want to slide tables together, to him it would be impossible to leave out the people on the ends and the servers should squeeze everyone in. For two tables, Damon drew this:

What I learned in that moment is that context and clarity really matter, especially if we want students to connect to the mathematics and grow their critical thinking skills. This problem in the most academic form is a standard linear growth problem — for each table add two chairs. Damon’s interpretation of the problem based on my explanation of families going to dinner together led him to see the problem in a different and beautiful way. Damon needed to include everyone, because that’s what happens in his family. I am indebted to Damon and the light he shined for me that day. I learned that how I talk about a problem needs to be clear — if I clearly talked about adding chairs before the family sat down together to eat, I wonder if Damon would have made sense of the context that I planned for. Second, I reflected and thought about how for some students who come from families and cultures that focus on inclusion and community, these types of problems that rely on shared cultural norms may not be interpreted in the same way when our cultural norms and beliefs vary. Can I go so far as to say this is evidence of a colonized curriculum in mathematics? Probably not. But I am pausing to think about how I can blur the lines between “school math” and reflecting students’ lives purposefully in the mathematics curriculum.

As a woman of Indian cultural heritage, I too can relate to how Damon understood this problem. For some communities and cultures, the norms around eating and communal gathering dictate that everyone should be included; and we can always say, “they can fit.” Growing up in an Indian family, our outings and social gatherings always included everyone, the elderly, the children, and the parents. We did not leave anyone out, and if we needed to move a little this way or that way to ensure everyone had space to sit and eat at a table, we did.

The conversation with Damon was so powerful for me because I could draw a distinction between an academic interpretation of the chairs and tables problem and the reality of children and families from diverse cultural backgrounds going out to eat. I continue to wonder about how to bring in more context from students’ lived experiences to add richness and love to the math classroom. When children feel that their lives are reflected in the content in math, they are more likely to engage and persist in problem-solving. I will be more careful in the future, as I think about the tables and chairs problem and other problems like it.