Summer, 2023

Some might think being antiracist is about confronting overt racism in curriculum or school policies but there is much more to it. Being antiracist as a math teacher is about recognizing how hierarchical power dynamics in the classroom mimic the ways bias and racism operate in our society. Ibram X. Kendi claims, “Becoming antiracist requires every individual to choose every day to think, act and advocate for equality, which will require changing systems and policies that may have gone unexamined for a long time.” (Schwartz, Interview with Kendi, 2019). Therefore it is antiracist in practice if math teachers act for equality by changing teaching practices and classroom policies that have long gone unexamined, actively shifting the power dynamic from teacher in control of students to one where learners, including the teacher, are in control of the learning together.

The Tug-of-War task is one of many that can be used to practice antiracist teaching strategies in the math classroom. What characterizes this task as a worthwhile option is the openness of the task, the lack of a prescribed solution pathway, and the easily accessible and relatable context. This task is adapted from a unit of study called Math In Context: Comparing Quantities (pp. 3, 2003) for middle grades. The unit is an introduction to algebra and explores several strategies to determine unknown quantities. All the standards for mathematical practices (SMP) could be explored through this task, but especially SMP 1, “Making sense of problems and persevere in solving them.” Antiracist teaching strategies in the math classroom are those that empower all learners to take the lead in sense-making, recognize the brilliance in one another, and break the cycle of sorting and filtering students based on racial identities and perceived abilities. In this article, antiracist teaching strategies are described in the context of facilitating this task through the launch, student work analysis, and whole group discussion.

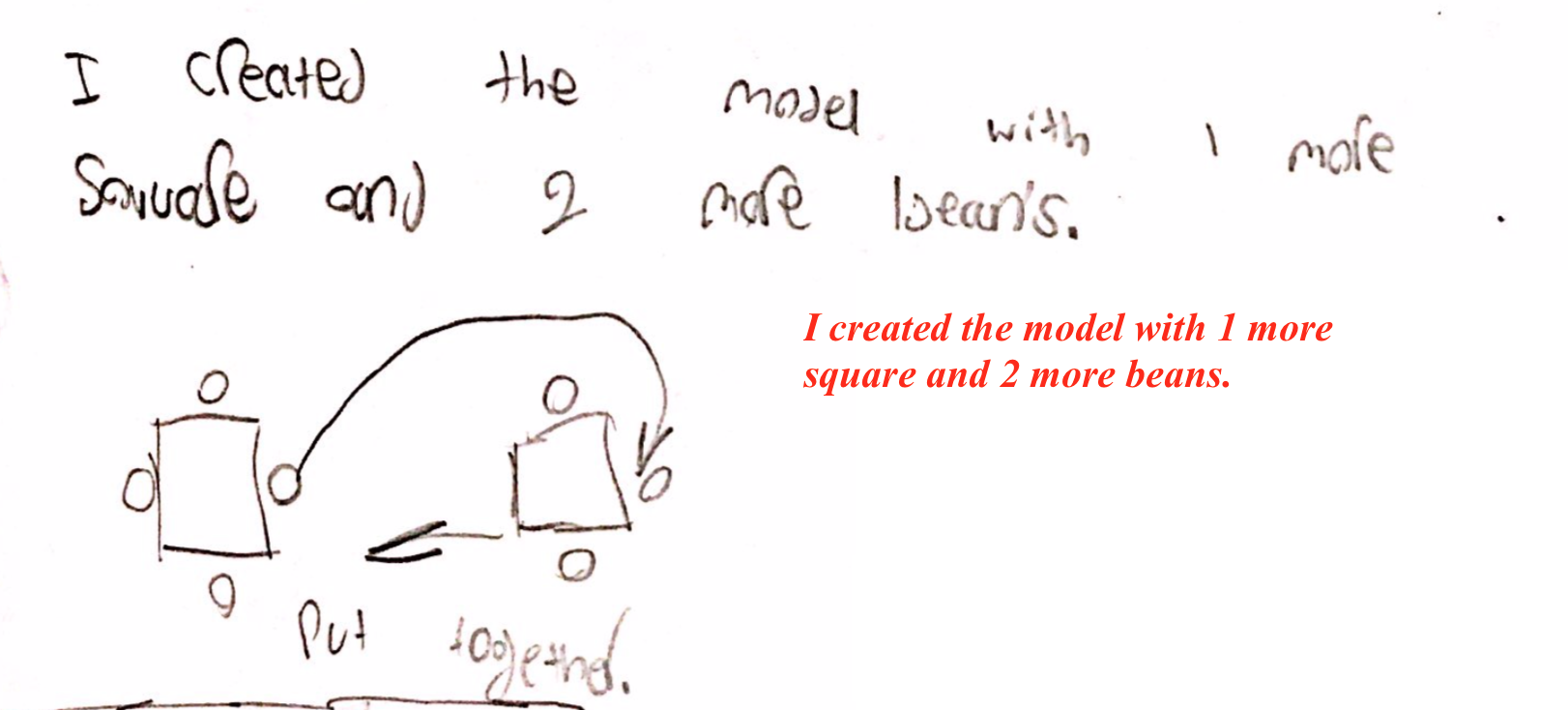

Figure 1: The task

Launch

A typical launch might involve a teacher explaining a concept or steps to follow. Instead the teacher can launch this task with a few words and puzzle alongside students. The image in Figure 1 is displayed on a shared visual space, e.g. projected on a whiteboard and students are asked who has played tug-of-war before. The teacher is not explaining the image nor are they describing the work product yet. Spending time on establishing a clear and shared understanding of the game itself is crucial to developing a deeper sense of mathematical equality in this context – when there is a tie there are no winners and both sides are balanced in strength. This adaptation removes the names of the animals and statements of equality from the original task (e.g. “four oxen are as strong as five horses”) and replaces them with shorter phrases e.g. “it’s a tie!”

It is important to remain neutral during the launch and check for understanding from all students. The teacher should avoid sharing their own noticings disguised as questions, e.g. “Do you all see that the elephant is the strongest?” The teacher must refrain from confirming or disconfirming any responses to what students conjecture is the problem to solve. For example, students may ask “Isn’t the elephant the strongest?” or “Isn’t the third one a tie too since it’s four animals versus four animals?” Some examples of a neutral response are “What do others think?” or “What makes you think that?” or better yet, nodding and remaining silent and simply letting people think about what was said. Students should not raise hands and share in the whole group until there has been sufficient time to work independently and in partners. Often there are known “smart” students in the classroom and once they speak, other students may shut down and disengage with the problem. Ilana Horn (2012) calls this a “status hierarchy” where the “smart” students are assigned more power than others in the classroom and could inadvertently control the pace of learning in a lesson. Instead, the teacher can consider asking all partnerships to contribute noticings and conjectures to the group conversation after everyone has had sufficient time to think.

The launch strategies above challenge the belief that the teacher is the source of control and knowledge and that some students are meant for math and others are not. When the teacher remains neutral in the launch the message is sent that everyone’s contributions are worthwhile and the teacher is positioned as a member of the problem-solving community, effectively saying, “I am with you in this effort.” Practice can shift away from the typical one-way dialogue between a teacher and student and instead invite discussion from all others in the space. The launch ends with articulating the question, “Who wins the final tug-of-war?”

Analyzing Student Work

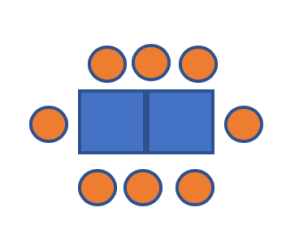

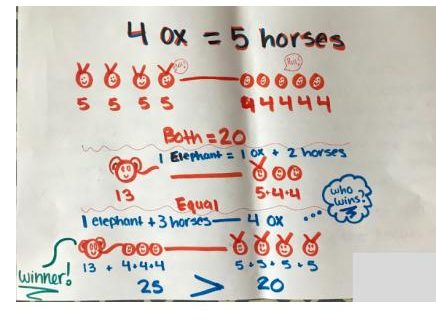

To orchestrate a meaningful discussion about different solution pathways, student work is collected, analyzed, and then presented back in a sequenced order on the following day (Smith & Stein, 2018). The learning target in this instance is to represent scenarios using equations and variables and construct viable arguments connecting the strategies presented. (HSA.SSE.1: Interpret expressions that represent a quantity in terms of its context. HSA.REI.1: Explain each step in solving a simple equation as following from the equality of numbers asserted at the previous step, starting from the assumption that the original equation has a solution. SMP3: Construct a viable argument to justify a solution method.) In the ninth grade class from which the sample work is taken, a total of eight artifacts were collected and three were chosen to display during the whole group discussion.

There are two connections across the three samples worth drawing out to support the learning goals. First, the strategies for working with equality are different. In Samples 1 and 2 the solution paths differ in terms of assigned values. In Sample 1, the values are assigned for each animal first (an ox is worth 4 and a horse is worth 5) and in Sample 2, the value for equation 1 is decided first (100=100) and then the values of oxen and horses are derived. Second, in samples 1 and 3, the authors model the animals but in different ways. In Sample 1, the animals are represented pictorially and in Sample 3 the equations are modeled using variables (see pink text). Comparing these two samples of work provides an opportunity to connect the pictorial representation of four oxen with the value “4x”, five horses with “5y”, and so on.

Studying student work and selecting samples to discuss in a specific order is a departure from the practice of grading student work and handing it back. Grades have long served in the process of ranking and sorting students by performance (Deshpande, 2015). In this process, students are not given grades after the first day and instead are invited into the process of giving feedback for the purpose of learning on the next day. Lesson planning in this instance involves strategizing how to highlight student voice, empower students to make their own mathematical connections, and shift practice away from using a textbook to using student work as curricular material.

Sample 1: Substitute values for animals in first equation

Sample 2: Set sides equal to a value in first equation

Sample 3: Model with equations

Whole Group Discussion

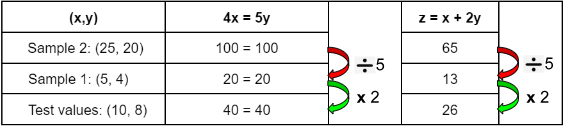

The second day begins with projecting work samples on the board and discussing them one at a time. To keep track of ideas the teacher should document the connections students are making on the board and try labeling ideas with the students’ names. The small step of assigning student names to their ideas can bolster confidence and confirm that students are contributing members of the math community. As predicted, the students connected “4x” and the drawing of four oxen and “5y” to the drawing of 5 horses, as follows in Table 1. Finally, the third tug-of-war is assessed in two ways, by substituting the values from Sample 1 (outcome 25>20) and Sample 2 (outcome 125>100) into the equation from Sample 3 which is z + 3y ≠ 4x. Spoiler alert: one elephant and three horses are stronger than 4 oxen (z + 3y > 4x).

Table 1: Making connections between pictorial and algebraic representations

In this particular instance, what happened next was not predicted! The students pushed the conversation into modeling substitutions and observing multiplier effects, see Table 2. Students worked with two equalities and three variables, deepening their understanding of how quantities can vary in proportion to one another in linear systems of equations. This was also a perfect opportunity to model using a table to keep track of student observations. By the end of crafting the table, some students asked a new question, “What are all the possible values of x, y, and z?” Ultimately, the students met the learning goal to model with equations and variables by the end of the lesson and furthermore ended with a new question to explore. A robust and lively discussion took place in which students were doing the “heavy lifting” to make connections across representations.

Seeing multiple ways to solve the same mathematics problem not only builds students’ problem-solving toolkits but also requires that students and teachers acknowledge and honor each other as equals on a level mathematical playing field. It has been shown time and again that students of color largely receive a subpar education as evidenced by persistent gaps in academic outcomes and access to opportunities (e.g. Mervosh & Wu 2022) so it is of the utmost importance that teachers practice the skills necessary to treat all students in their classrooms equally and fairly. The reader might ask, how is this considered antiracist especially if a teacher is teaching in a racially homogenous classroom? The answer is that classroom practices do not happen in a bubble, and how different abilities and approaches in the math classroom are honored is parallel to how the contributions made to any community e.g. workplaces, neighborhoods, cities, etc. by persons of any race, nationality, (dis)ability status, gender orientation, and other social identities are honored. According to Kendi (2023), antiracism is about shifting from focusing on the individual or group to focusing on the outcome, so the focus in this moment is on honoring how solution pathways can be vastly different and the result is the same, equal outcome.

Conclusion

Being antiracist is about challenging any policies and practices that position people in false hierarchies. It is not always about confronting overt forms of racism. By engaging in antiracist teaching, teachers can confront long-standing biases against various communities of color by questioning their assumptions and making good faith efforts to employ some of the strategies described above. Practicing antiracism in teaching is about practicing how to genuinely honor and value students’ contributions regardless of their racial backgrounds, past performances, or perceived abilities in math.

References

Boaler, J. (2015). Mathematical mindsets: Unleashing students’ potential through creative math, inspiring messages and innovative teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Deshpande, A. (2015). Making the Grade: Exploring the variability of grades and teacher beliefs about grading in New York City public middle schools. Doctoral Dissertation. New York University.

Driscoll, M. (1999). Fostering algebraic thinking: A Guide for teachers, grades 6-10. Heinemann.

Emdin, C. (2016). For White folks who teach in the hood… and the rest of y’all too: Reality pedagogy and urban education. Beacon Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder, New York.

Goffney, I., Gutiérrez, R., & Boston, M. (2018). Rehumanizing mathematics for Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Horn, I. S. (2012). Strength in numbers. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Kendi, I. X. (2023). How to be an antiracist. One world.

Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press.

Mathematics in Context: Comparing Quantities. (2003). Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Mervosh, S., & Wu, A. (2022). Math scores fell in nearly every state, and reading dipped on national exam. New York Times.

Schwartz, K. (2019). Interview: How Ibram X. Kendi’s definition of antiracism applies to schools. KQED.

Smith, M., & Stein, M. K. (2018). 5 Practices for orchestrating productive mathematics discussion. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.